by Mongabay.com on 10 September 2021

- Mountain forests store nearly 150 metric tons of carbon dioxide per hectare, a new study estimates, which is more than the Amazon Rainforest per unit area.

- The U.N.’s leading scientific body on climate change, the IPCC, pegs the default value for these forests at 90 metric tons per hectare, underestimating their role in regulating the planet’s climate.

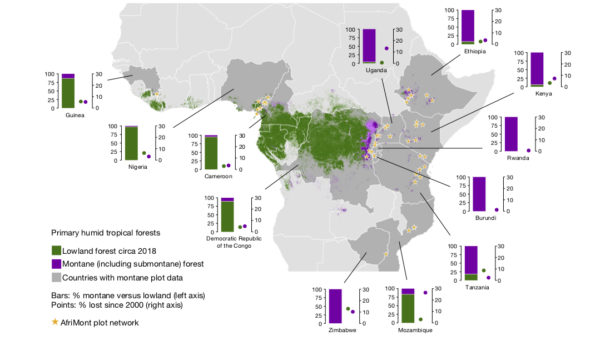

- High-altitude forests cover 16 million hectares (40 million acres) of land in Africa, primarily concentrated in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but about 5% has already disappeared since the turn of the century.

- The study authors say they hope the new estimates will make these forests more attractive for carbon finance initiatives.

A new study promises to give Africa’s mountain forests a leg up in the eyes of climate scientists. They store nearly 150 metric tons of carbon dioxide per hectare, according to the authors. Hectare for hectare, that’s more than the Amazon Rainforest.

The U.N.’s leading scientific body on climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), pegs the default value for these forests at 90 metric tons per hectare. That’s a serious underappreciation of their role in regulating the planet’s climate and could play in the future, the study indicates.

“The results are surprising because the climate in the mountains would be expected to lead to low carbon forests,” lead author Aida Cuni-Sanchez, from the University of York, U.K., said in a statement.

The analysis published in Nature looked at 225 plots of old-growth montane forests in 12 African nations, making it one of the most comprehensive surveys of its kind to date. The remoteness of many of these forests is one big reason why continent-wide studies are hard to find.

Nicolas Barbier at France’s Université de Montpellier, who wrote an accompanying commentary in Nature, called the study “remarkable” in its scope. However, Barbier noted that the area covered in the survey was 100,000 times smaller than the area covered by these forests in Africa: 16 million hectares (40 million acres).

The authors collected measurements — trunk diameters and heights — of 72,336 individual trees. With this data, they were able to calculate aboveground carbon stores. They did not account for soil carbon.

Montane forests’ undervaluation as carbon sinks has to do with size. With lower temperatures and persistent cloud cover, botanists expect trees at higher altitudes to be smaller. Strong winds and treacherous slopes also constrain how big trees can grow before they topple over. The discovery of some of Africa’s tallest trees on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania challenged this understanding.

It isn’t clear yet why they turn out to be so hefty.

The abundance of large trees, with trunks more than 70 centimeters (28 inches) in diameter, in mountain plots is one reason for their carbon richness.

But the forests are worth more than their weight in carbon. Africa’s two great rivers, the Nile and the Congo, originate in these high-altitude woodlands. The Nile’s two major tributaries arise in highlands in Ethiopia and Burundi, while the Congo River traces its origins to the mountainous belt of the East African Rift.

The isolation and change in elevation create niche habitats. Without the mountain forests, there would be no mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei). These great apes are found only in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Uganda and Rwanda. The DRC hosts two-thirds of Africa’s montane forests.

For 10 countries on the continent, most of them in East Africa, almost all their mature forests are found in mountainous regions.

About 800,000 hectares (2 million acres) of montane forests in Africa have disappeared since the turn of the century. The DRC reported the highest losses. Mozambique lost a third of its montane forests between 2000 and 2018. At this rate, another 500,000 hectares (1.2 million acres) of mountain forest cover will be gone by 2030.

“We hope that these new data will encourage carbon finance mechanisms towards avoided deforestation in tropical mountains,” Martin Sullivan, a co-author of the new study and ecologist at Manchester Metropolitan University, U.K., said in a prepared statement. “As outlined in the Paris Agreement, reducing tropical deforestation in both lowland and mountain forests must be a priority.”