Across Africa’s higher education sector there is an awareness that the fourth industrial revolution is here. Educators now have a tremendous responsibility to prepare the people and organisations of the continent for a time of rapid change.

It can be argued that in the time of Industry 4.0 the stakes are higher in Africa than anywhere else in the world. Africa’s economic development has been accelerated by an ability to harness technology to leapfrog developmental steps in multiple industries. However, in a continent where many places have never seen the benefits of Industry 3.0, there is a danger of many being left behind as the demands of industry no longer match the skills available in the workforce.

Technology has the power to uplift millions of Africa. Similarly, it carries the threat of leaving millions more unemployed and locked out of the global economy.

How is the higher education sector preparing young Africans for an uncertain future? And how can Africa ensure it remains globally relevant in the fourth industrial revolution?

_________________________________________________________________________

“The global crisis we are experiencing right now I believe, is showing us the need for universities.

“The global crisis we are experiencing right now I believe, is showing us the need for universities.

I am working on a paper that will be titled “the return of the expert”. The paper takes into account the disillusionment of people when it comes to higher education in the past few years. It was almost like corporates and industry as a whole, were losing confidence in universities. There were many complaints about the calibre of graduates we were producing and our research. People like me have been at pains to defend the sanctity of basic research. Covid-19 is a horrible pandemic, but it also provides an opportunity for the expert researcher.

Our work has been questioned over the years but now in the current crisis business has no solution, government has no solution, so its upon us. Universities are the ones grappling with trying to find a vaccine, as well as taking an in-depth look at our business models. We are looking at our business models to determine if we should maintain them. Covid-19 highlights the importance of the expert, scientist and scholar. What we do will be valued more than it has ever been in recent times. I, therefore, do not see the relationship between universities and the private sector deteriorating in any way in the future. If anything, our relationships will only get stronger and more funding will become available for universities. Our partnerships cannot loosen, especially now. Businesses wants and needs a stable environment. A stable environment is not possible with the current public health crisis.

We have to produce results and solutions that prove our worth. A lot of anti-university sentiment in the recent past revolved around changing technologies. There was a lot of talk about universities needing to get with the programme or ship out in the face of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the fourth industrial revolution. It was not very comforting because these advancements are not taking place independent of us. A lot of the technological advancements have been born in universities, we are part of the revolution. We are in the business of new knowledge and research, just because corporates may fund them does not mean we don’t have a voice.

A lot of the challenges I foresaw with regards to industry relationships will not be a thing in the post-Covid times because I see us forging tighter partnerships. We currently even have researchers working on advancements beyond Covid which involve transportation, town planning and a few other areas. Our intellectual capital will be invaluable to corporates and industry.“

Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng, Vice-Chancellor, University of Cape Town. South Africa

“The rate of change means there is going to be huge disruption in multiple industries; higher education is just one of them. The real challenge of our time is to start experimenting now rather than waiting for a complete set of mature technologies and then deploy them.

What we have done most obviously is to reform and think through the curriculum with respect to technology and how it is going to change the professional disciplines. If you go to our computer science or software engineering programmes, there are new courses we have developed in this regard. However, even if you are to go to traditional programmes which you would not see as technologically grounded such as journalism then you would also see huge curriculum reform introducing people to social media, to new forms of distribution, to discussions on the new ethical boundaries we would need to think through.

It is important as we go forward in this new era to not create a new form of inequality in which poor people get online education and rich people get face to face education. That is not what we want to create, we want to create a much more complex and nuanced delivery of educational possibilities. Some people might start online and then move to face-to-face and use all of these possibilities in a complex structure. That is something we will be moving towards in the next twenty to thirty years and that is something we should be experimenting on now. We are one of the few who are at the cutting edge of that experimentation.”

Prof. Adam Habib, Vice-Chancellor, University of Witwatersrand. South Africa

“In Africa, we are struggling to respond to the rising demand for higher education. We must supply not only enough educators but also a relevant curriculum. Our young people who make up the majority of the population are growing up in a digitised world. Using technologies that they are already familiar with in teaching, will go a long way in preparing them for what’s coming. We have platforms like Engineering 4.0, Future Africa Chambers, as well as innovation Africa. These platforms have enabled us to come up with concepts like precision agriculture which reduces water wastage and tackles food scarcity. If we can build on these platforms and infuse technologies, methodologies, and applications for the fourth industrial revolution; we can easily succeed. It is necessary to bring in different stakeholders to co-create new knowledge that sustainably addresses societal problems.

We want to enhance intra-African cooperation by building ourselves up as the African Global University. We are a member of the African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA), which has helped establish bonds with other campuses in the region. Our institution is also part of the Australia- Africa partnership since we want to foster relationships both at home and abroad. The need to collaborate more domestically cannot be understated. That is why we joined the African Alliance Partnership, made up of ten institutions from the continent. The University of Pretoria is also part of FANRPAN, which is a policy advocacy group for agriculture and natural resources. When more African institutions join these initiatives, you will find intra-African networks developing organically.

The future of African education must hinge on quality in terms of research, teaching, infrastructure, and working environment. The thirst for knowledge amongst our bulging young population is only getting stronger. We must adapt and provide the resources necessary to cope with this demand. It will be upon us to mobilise resources, increase engagement and collaboration, boost tech capacity, and make curriculum relevant.“

Prof. Tawana Kupe, Vice-Chancellor, University of Pretoria. South Africa

“We must support innovation and promote it as much as we can. Our member universities, as well as those in Sub-Saharan Africa, are very cognizant of this. You are now seeing many schools set up incubators and encouraging entrepreneurship. That will create an environment which allows graduates to set up a business based on innovation and new ideas. As an institution, we are very serious about transformational learning to prepare graduates not just to seek jobs but create them.

Many jobs will indeed vanish, but new ones will also come up. It won’t be a matter of a scarcity of employment but how Universities can train people for the jobs that will come up. Academia must be very close to the industry so that our work benefits society.“

Dr. Amr Ezzat Salama, Secretary General, Association of Arab Universities. Egypt

“It all starts with leadership.

To be successful in the time of the fourth industrial revolution organisations must be able to adapt, be able to innovate, and able to collaborate. This is very important; it all comes down to leadership.

We phrase it as collaboratist leadership. Collaboratist leadership is super transformational leadership. That is what we need in organisations for Industry 4.0

By far the most important things in Industry 4.0 are trust and support. We call it trustworthy support, and this includes integrity, competence, consistency, and openness.

Openness is required from leaders for teams to share ideas and information freely when you collaborate.

Integrity is required from leaders, and this is extremely important as this is where ethics come in.

If you do not have leaders on board who are honest you are going to have problems. They need very good judgement in handling new situations, which is where consistency comes in.

We live now in the time of innovation. The key to this time is collaborative innovation. The collaboratist leader must encourage innovation and must encourage teamwork.

The problem we have is that our students come back to us after they have returned to work and tell us there are serious problems. When they try to implement these wonderful ideas they have learned around Industry 4.0, leadership, changing supply chains and governance there is resistance from the top.

This mindset is the problem. We need to get rid of the old paradigms. If we do not have leaders that can adapt then we are going to be in big trouble.

It seems some leaders are almost scared of Industry 4.0. We can only correct this situation through education.“

Prof. Pieter Steyn, Principal and Founder, Cranefield College. South Africa

“The fourth industrial revolution will be all about interconnecting processes, industries, and institutions through new technology.

Bearing in mind that there is a global reduction in higher institution funding, it is prudent to use technology to utilise resources efficiently.

African institutions of higher learning have a duty to create spaces that foster ideation, innovation, and incubation of ideas that will develop into technological solutions.“

Prof. Munashe Furusa, Vice-Chancellor, Africa University. Zimbabwe

“How do we work with business to confront and navigate major technological disruption?

“How do we work with business to confront and navigate major technological disruption?

How do we do that in a continent where we can’t assume that the demands and challenges of the third industrial revolution have already been met?

If we are not alert to the way that technology is being rolled out globally, then in Africa we will find ourselves only being consumers of these technologies. That would represent a missed opportunity to be part of the global value chains that are associated with actually producing and delivering these technologies.

You can’t set up an insolated think tank to deal with this. You need to embed it across curricula. This is hard in institutions where academia is seen as having the answers, I think the role of academia is to ensure that we are asking absolutely the right questions and to be working towards finding those answers.”

Prof. Nicola Kleyn, Dean, Gordon Institute of Business Science University of Pretoria. South Africa

“We must not try to emulate or copy what is practised in economically advantaged parts of the world. If we follow behind Western institutions like Cambridge, Oxford, and famous French Universities we will be in trouble. Copying those institutions means we will always be behind them. I have seen this copycat model of education in South East Asia as well, where they copy the education system in places like Finland. This model just doesn’t work because everything is different, the funding, the geographical location, and the perception of education.

African regions must turn the education system on its head and confidently create their versions of higher education. Sadly our education system is based on what happened in ancient Greece and Rome. We have to revolutionise it in a way that takes stock of Africa’s challenges and opportunities. In Africa, we have developed an appetite for E-learning. E-learning can be quite useful except I am not a fan of it. I am a big advocate of deep learning which involves face to face learning. This way of learning in my view is more effective than e-learning.

Africa also needs to confront the gender disparities that exist. On this island, for instance, we didn’t see a lot of female representation as far as the candidature. We, therefore, need to push for more female representation in leadership, education, and in the workplace. If we get it right, Africa can be a leader by doing things differently.

Mauritius has already put this in motion through its free higher education programme. This is better than the system in most of the UK where families have to go deep into debt for children through higher education. Education needs to be democratised and seen as a right and not a commodity, just like this island has done. We must be wary of post-colonial opportunists who come to Africa to make money by offering watered-down education. These postcolonial opportunists often offer an education that is of lesser quality than what is being offered by poorly funded local schools. There is, therefore, a need to curb this mentality of education being a commodity. We must also stop seeing foreign students as cash cows. I will make it a priority to ensure that foreign students who come to this institution are charged the same as the locals.

A good spotlight on education is great because it is the most important thing on the planet. If we are conscious of what is going on and how it affects us, we can change the planet. The public perception of education in Africa right now provides an opportunity for Africa to be a leader in education. This is because Africa will do things her own way and I will be delighted to be part of that.“

Dr Keith Robert Thomas, Director General, University of Technology. Mauritius

“The fourth industrial revolution is upon us and a lot of industries will be disrupted. This digital economy will enable someone sitting in Chad to sell a pair of shoes to someone in Guatemala. To get to that point, we must do a lot to improve our connectivity infrastructure. I feel that Africa is the laboratory of the digital economy because it is very advanced when it comes to digital transactions.

Africa can, therefore, handle the changes that will come thanks to the fourth industrial revolution. Western models are not necessarily tailored for African economies. We feel like we are supposed to run our organisations, and our education the way the west does it. We have to realise that our economic structure is completely different. We have to educate people in a way that suits our needs.

Educating our people in our own way does not mean that we veer away from global standards. We must stay updated and competitive. Globalisation will help a great deal with that. This is because our people will have access to education from other sources. This way they will not have to just depend on local educational offerings to get ahead. Students will be able to expound on what they already know and learn what the local system may be late to teach.

Education will look very different in the future. People will be able to monetise any skills through the internet. Someone in the Ivory Coast who makes shoes will be able to sell them to someone in Poland, for instance. Payment products like the one we have at Wari will facilitate these transactions. This globalisation will essentially wipe out borders. There will be no Africa, China, or Europe because we will be able to trade skills, information, and products. People in Lagos, for instance, will be able to source for skill in Europe if they can’t find it locally.“

Kabirou Mbodje, CEO of Wari. Senegal

“Our primary focus now can be described as ensuring better preparation for the future and for the digital world.

“Our primary focus now can be described as ensuring better preparation for the future and for the digital world.

This will encompass everything from renewable energy to dealing with data sciences for business to internationalisation.

Obviously, renewable energy is very important for a country like Morocco which doesn’t have a lot of oil and the energy that we produce is expensive. With solar, biomass, and wind power we can save the planet, save the environment and save the economy as well.”

Prof. Driss Ouaouicha, Vice-Chancellor, Al Akhawayn University. Morroco

“Innovation is at the centre of our goals. The University should not be considered the centre of our work, innovation is at the centre and the University is a partner in developing innovation. This is an important mindset shift.

We are working with a significant number of companies to build our business capital and jointly develop research.

The mindset is all about opening up the University and not being in that ivory tower. It is about opening the university to industry and opening the university to the community.“

Professor Dhanjay Jhurry, Vice-Chancellor, University of Mauritius. Mauritius

“Collaboration is the key to the future of our University and our country.

Our role at present is to create an intellectual atmosphere within the country and attract companies to join us in building this atmosphere. Now is the time for Unisey to start building capacity for the country as well as the region by creating research that contributes to the main pillars of our economy – tourism, hospitality, blue economy, environment and financial sector.”

Our major strategic goal is making Unisey a national project and building connections both locally and internationally. As an institution that is only 10 years old, we need partners to grow. We need to educate people on the critical role we will play for the future of our nation. It is crucial to spark a conversation amongst businessman, educators and policy-makers as to why they need to fully support this university. Together we can build the local knowledge within the country and make higher education accessible to a larger group of people.”

Dr. Justin Valentin, Vice-Chancellor, University of Seychelles. Seychelles

“Technical universities in South Africa do not focus on research. In my opinion, innovation and research should be at the core of universities providing technical education.

“Technical universities in South Africa do not focus on research. In my opinion, innovation and research should be at the core of universities providing technical education.

The main focus is to put the knowledge into use. We are not interested in essays and paragraphs, but in results. Our strategy is based on the traditional slogan “publish or perish.” We use an improved version known as “collaborate or collapse.”

Being a new-generation university, we have less resources as compared to well-established Universities. We are moving towards the quadruple helix approach. This approach will help establish a meaningful interaction between the government, universities, private sector, and our communities. A real, strategic, and vibrant collaboration between these entities is required.”

Professor Lourens van Staden, Vice-Chancellor. Tshwane University of Technology. South Africa

There is an acceptance that industry leaders and universities must work together to find solutions and prepare for change.

Now more than ever before, industry is opening up to us and we are opening up to industry. We need to engage with industry captains and find ways how we can have our Ph.D. students embedded in their organisations. We wish to have industry leaders attend our seminars and be involved in our projects and policy briefs in order for us to conduct research relevant to the private sector.

We must help industry build their staff and research capabilities and we are actively pursuing new partnerships at present. We use our faculty and our alumni to connect with industry. We have a dedicated team to engage with policy response teams so we are able to have an immediate response to any issues that come up in the corporate world.

Professor Justice Nyigmah Bawole, Dean, University of Ghana Business School. Ghana

“Any perception that African universities and organisations are completely unprepared for the future is inaccurate.

“Any perception that African universities and organisations are completely unprepared for the future is inaccurate.

I think the world doesn’t know about the knowledge and new inventions that are being generated in Africa and we can only blame ourselves for that. If you look at that new knowledge creation from the public and some private institutions in South Africa, I firmly believe that South Africa is making a significant contribution to the world.”

I believe there are indeed great initiatives in Africa and it is in our hands to show to the rest of the world that we are on par and that there are many unique pockets of excellence in which we are competing and in some cases doing better than the rest of the world.”

Professor Henk de Jager, Vice-Chancellor, Central University of Technology Free State. South Africa

“The notion that the fourth industrial revolution will affect everybody, and their job is both true and false.

“The notion that the fourth industrial revolution will affect everybody, and their job is both true and false.

We don’t refer to it as the fourth industrial revolution because that makes it unclear to many people. In our eyes, we interpret it as a time with increased connectivity, better software development, artificial intelligence, as well as other technologies that redefine the world of work.

Though some manual jobs will be lost, we must not see the fourth industrial revolution as a threat but rather an opportunity to diversify our economy.

We are training students in the fourth industrial revolution competencies so that they can go out there and build new industries. Corporate players also need to take part by investing in these new industries. These are the discussions we are having with industry players.“

Jon Foster-Pedley, Dean and Director, Henley Business School. South Africa

“There is now a debate around the place business schools have in the world.

Business schools have had a hard time due to a popular misconception that they only serve the agenda of businesses and pursuing profits. African business schools have come to realise that their role is much bigger than just reproducing knowledge and people for the world of work. They also have to add value, therefore it is important for business schools to theorise the role of business and then the role of business schools in their space.

The role of business is a social justice role. Business is the applied economy and all of us participate in economic life. Business must serve toward the prosperity of human beings. Once we understand that, then we can train individuals to become the citizens our world needs.“

Dr Randall Jonas, Director, Nelson Mandela University Business School. South Africa

“The fourth industrial revolution will built upon disruption. Technological advancements will also play a huge role. The biggest disrupter though is Africa’s bulging young population.

“The fourth industrial revolution will built upon disruption. Technological advancements will also play a huge role. The biggest disrupter though is Africa’s bulging young population.

Africa is currently seeing a youth bulge similar to the one that was seen in Asia back in the eighties and nineties. We have millions of youth below the age of twenty-five. These youth have needs and aspirations, and we are struggling to meet them. Business schools are trying to figure out what these youth should be learning, and what credentials they need to impact their economies. If African institutions of higher learning fail to draw effective curriculums for the twenty-first century, our relevance will be in question.“

Dr. Ahmed Shaikh, Managing Director, Regent Business School. South Africa

“Education is going to be massively disrupted by the rate at which industries are changing. People are going to have to retool constantly after they enter the job market. In the past, you could work a job in your area of training without much need for diversification of skills. Things are vastly different today because industries are continuously demanding new skills. The new skills being demanded are, most of the time, quite different from a professional’s area of training.

Our institution works very closely with Ghanaian industries in several ways. First, we ensure industry involvement in your curriculum design and review processes.

We constantly survey industry to follow up on how our students are doing in their internship and permanent placement jobs. The feedback we get from interns and alumni in corporate Ghana is used to inspire changes in our curriculum where necessary. Our institution keeps up with how automation is changing our industries. There has been a lot of fear that automation may kill jobs. What we may not realise is that automation may lead to the rise of jobs we don’t know of yet.

It would do us good to worry less about automation, and instead focus on research. This research has to be relevant to our situation so that our industries flourish.“

Mr. Patrick Awuah, Founder and President, Ashesi University. Ghana

“We need a radical shift to keep up with changing technologies in this era of the fourth industrial revolution.

Often, when it comes to technology in Africa, we find ourselves in the back seat. We must react much quicker in the face of changing technologies, especially where production is concerned.

This reaction will have to be spurred by policies both at the institutional and government level. In our case, institutional policies are often guided by government policies. This works against us at times because government policies are often behind the curve. Our local regulators, for instance, want to revise our curriculum every five years. This is problematic because we all know that industries are changing at a much faster rate than that. We want to be able to keep up by making changes way sooner.

The fourth industrial revolution is upon us at a time when Africa has an enormous youth bulge. We have to respond to the economic needs of our youth by encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship. We have made those two topics compulsory here at the International University of Management in Namibia, at least for the first two years into all student programmes. Students then decide whether to continue on that path or not.

However, even as we make efforts to adjust accordingly in the face of the fourth industrial revolution, we must remember that some things will always remain as they are. We will always need food and shelter, so our innovations and research must centre these two key areas. We must emphasise the need for smart farming in rural areas and research ways to improve housing for our people.“

Prof. Kingo Mchombu, Vice-Chancellor, International University of Management. Namibia

“The type of education we currently have, which emphasises theory over practice, has failed Africa. We have to adopt a brand of education that will help us industrialise through technical and vocational training. Founder of the World Economic Forum Klaus Schwab once said that talent will be the capital of tomorrow. His words speak to the fact that technical and vocational universities will play a major role in skill acquisition on this continent.

African higher education institutions need to present themselves as resourceful. We should come across as partners in development as opposed to institutions that are charity cases. When we come up with solutions to the problems in our communities, we will easily attract funding both from international well-wishers and local industry.

I want the Cape Coast Technical University to be seen as an innovative university, a university that takes innovative approaches and does not just stick to the traditional ways of doing things. We also want to build the image of an entrepreneurial university that produces builders of the economy who will have an impact at the local, national and international levels.“

Ing. Prof. Joshua Danso Owusu Sekyere, Vice-Chancellor, Cape Coast Technical University. Ghana

“In the age of the fourth industrial revolution, there is a rapid evolution when it comes to skills required. As a university, we have to start teaching data science as a new area. I bet that will change in the next two years and we will be required to upgrade that.

Most universities will struggle to keep up with these swift changes in skill demand. We will then become institutions that teach the basic principles and fundamentals of new areas. I foresee new institutions belonging to the private sector that will then be formed to carry out rapid skill transference. Good examples of collaborations with individual institutions for the imparting of skills are Udemy and Udacity. I foresee a parallel education system outside the traditional universities, that will come in and train on fast-changing specializations.

The higher education system in Africa will face significant disruption because of two factors. One will be the push factor. Africa is set to have the youngest working population in the world in decades to come. Analysts have predicted that the rest of the world will have to go to Africa for human capital and skills since we will have a large working-age population. This youth bulge will push institutions of higher learning to invest in better programs, better technology, and relevant skills. The second factor will be the pull factor. Africa’s higher education institutions have no option but to adopt new technologies and deliver quality programs if they are to pull students into their schools. Failure to adapt to the changing environment will render them irrelevant.

The earlier we recognize this and change the way we teach and conduct research, the better for our survival as institutions.

We want to have a robust research focus as an institution that will be propelled by our PhD program. We are looking into artificial intelligence technology as well as computer science. Our research focus is not just limited to the P.H.D level; our bachelor’s programs also form a basis for research.

We also need to attract private sector institutions to invest in our research projects, just like it happens in the developed world. We can do this by providing a value proposition that will ensure a symbiotic relationship.“

Prof. Clement Dzidonu, Vice-Chancellor, Accra Institute of Technology. Ghana

“Our policymakers must create a conducive environment for higher education institutions to do what they are supposed to do. Regulatory bodies in Nigeria have put obstacles in our way that have lessened our impact on society. I find them not as dynamic as I believe they can be in this day and age. We shouldn’t be unable to set up open and distance learning platforms because regulators insist on face to face learning. Regulators are failing us because the people who sit in those boards are not as progressive as current times demand. The situation requires that these individuals rise to the occasion and make necessary changes“.

“Our policymakers must create a conducive environment for higher education institutions to do what they are supposed to do. Regulatory bodies in Nigeria have put obstacles in our way that have lessened our impact on society. I find them not as dynamic as I believe they can be in this day and age. We shouldn’t be unable to set up open and distance learning platforms because regulators insist on face to face learning. Regulators are failing us because the people who sit in those boards are not as progressive as current times demand. The situation requires that these individuals rise to the occasion and make necessary changes“.

“African governments need to show more support for higher education. Our investment in higher education is way below what is recommended by international bodies like UNESCO. Private institutions have an advantage because their owners have the funds to make things happen. The federal government of Nigeria should start viewing private institutions of higher learning as stakeholders. The proprietors of those institutions will then be able to fill the funding gaps that the government may have. Such moves would change the education, ecosystem but it would only happen if policymakers make education a priority“.

Prof. Aderemi Atayero, Vice-Chancellor, Covenant University. Nigeria

“We realised years ago that there was an unfortunate disconnect between industry and academia. As an institution, we set out to find a solution that would promote more synergy with the industry. One of the answers came in the form of the Institute of Applied Science and Technology. We started that institution to help bridge the gap between academia and industry. It has worked well so far because engagements with the industry have been steadily increasing. Our efforts also include the formulation of a science pact with the government, which will help advance academia-industry meet-ups“.

“We realised years ago that there was an unfortunate disconnect between industry and academia. As an institution, we set out to find a solution that would promote more synergy with the industry. One of the answers came in the form of the Institute of Applied Science and Technology. We started that institution to help bridge the gap between academia and industry. It has worked well so far because engagements with the industry have been steadily increasing. Our efforts also include the formulation of a science pact with the government, which will help advance academia-industry meet-ups“.

“The government has also set aside large tracts of land for the development of industries close to our area. We will benefit immensely from new research and partnership opportunities when this materializes. Our PHD program is also undergoing modifications to become more industry oriented“.

“The rapid changes being brought about by technology are undeniable. Any institution that remains rigid in the face of change will fail miserably. I, therefore, advise our sister institutions to stay on the lookout and adjust accordingly. Technology helps save time and gives value for money at the same time, which is why our government is increasingly digitising operations. As a university, we are capitalising on technology to enhance disciplines like agriculture, teaching and research. Remaining relevant in this technology age is about adapting quickly“.

Prof. Ebenezer Oduro Owusu, Vice-Chancellor,University of Ghana. Ghana

“You have to be prepared and adopt a program to meet your future needs. It would be best if you were ready for an industrial revolution by following or being part of the development. We may be the third world, but in terms of education, we are one unit, and we have to bring those within this country. There are a lot of developments taking place, and we as Africans should not lag. Therefore, universities, colleges, and establishments have to get together and work so that they would be ready for an industrial revolution.

“You have to be prepared and adopt a program to meet your future needs. It would be best if you were ready for an industrial revolution by following or being part of the development. We may be the third world, but in terms of education, we are one unit, and we have to bring those within this country. There are a lot of developments taking place, and we as Africans should not lag. Therefore, universities, colleges, and establishments have to get together and work so that they would be ready for an industrial revolution.

We are getting our students prepared within the campus so that when they go to the industry for internship or attachment, they will be able to perform. The industries within Botswana may not be enough for all our students, and therefore we have to be somehow connected to other organizations and companies within the African region. Our students need to be able to learn and contribute to the industries within Botswana and the international community. We encourage our students, and I hope we will be able to achieve something positive from the New Era University College, which we can register in the future.”

E. Ghodrati, Founder and Managing Director, New Era University College. Botswana

“We are big on utilising our resources to the maximum and that’s the foundation of our philosophy. Our philosophy is described by two words in our Ndebele dialect, which are Kuziva ne Kugona. Kuziva means a deep understanding of one’s circumstances, environment, and opportunities. Kugona is about proficiency, competency, and capacity”.

“We are big on utilising our resources to the maximum and that’s the foundation of our philosophy. Our philosophy is described by two words in our Ndebele dialect, which are Kuziva ne Kugona. Kuziva means a deep understanding of one’s circumstances, environment, and opportunities. Kugona is about proficiency, competency, and capacity”.

“Our systems of education have been all about conforming to western ideals but this shouldn’t be the case in our higher institutions if learning. Our objective is to make our education system encourage us to be ourselves, this way we will delight in our authenticity and heritage. We cannot afford to uphold education systems that put western ideals on a pedestal. Our system of learning must be geared to eradicating poverty, underdevelopment and hunger”.

Prof. Paul Mapfumo, Vice-Chancellor, University of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe

“African institutions of higher learning need to build capacity in research and also build links with industry. We also need an open line of communication with policymakers so that they can have sufficient information as they draw policy recommendations. Our problems are similar across the continent, so it only makes sense to collaborate with other institutions. Collaborating builds capacity and enables us to train our people sufficiently based on Pan-African ideals. As we seek to develop, we must not forget to involve our people in the diaspora because their input is needed too. Our research efforts focus on communicable diseases as well as maximizing industry productivity. Research can help address both of these problems”.

“African institutions of higher learning need to build capacity in research and also build links with industry. We also need an open line of communication with policymakers so that they can have sufficient information as they draw policy recommendations. Our problems are similar across the continent, so it only makes sense to collaborate with other institutions. Collaborating builds capacity and enables us to train our people sufficiently based on Pan-African ideals. As we seek to develop, we must not forget to involve our people in the diaspora because their input is needed too. Our research efforts focus on communicable diseases as well as maximizing industry productivity. Research can help address both of these problems”.

“The future of higher education in Africa is bright because mindsets are changing. Collaboration is critical amongst all stakeholders to ensure we produce skilled graduates. Institutions must also believe in sharing expertise. Some institutions have more senior scholars than others; they should be allowed to serve more than one institution”.

Prof. Kalombo Mwansa, Vice-Chancellor, Cavendish University. Zambia

“We are not restricting ourselves to the four corners of the lecture room; we are embedding technology in everything that we do. The fact that you can take classes from work or home is evidence of that. Government intervention is also essential in making life much easier for education providers. An enabling environment will enable educators to provide quality education for the human resource base that they want to train”.

“We are not restricting ourselves to the four corners of the lecture room; we are embedding technology in everything that we do. The fact that you can take classes from work or home is evidence of that. Government intervention is also essential in making life much easier for education providers. An enabling environment will enable educators to provide quality education for the human resource base that they want to train”.

“Short courses for employees in tech industries are provided much to the delight of employers. It is up to those employees to make themselves available for classes or risk being redundant. We must ensure that we can educate our workforce by introducing them to continuous training and allowing them to attend short courses”.

Prof. Emmanuel Ohene Afoakwa, Vice-Chancellor, Ghana Technology University College. Ghana

“Institutions of higher learning must remind themselves that industries are profit-making entities. Our job is to demonstrate our worth or end up becoming redundant. If we cannot provide the services that the sector requires because they doubt our delivery or standards, they will seek out other institutions of learning. We must, therefore, understand our industries so that we can identify gaps that if filled, will make them more substantial profits. We have identified some issues in the mining industry and come up with solutions”.

“Institutions of higher learning must remind themselves that industries are profit-making entities. Our job is to demonstrate our worth or end up becoming redundant. If we cannot provide the services that the sector requires because they doubt our delivery or standards, they will seek out other institutions of learning. We must, therefore, understand our industries so that we can identify gaps that if filled, will make them more substantial profits. We have identified some issues in the mining industry and come up with solutions”.

“Our research successes in the mining industry have helped us build great partnerships that further our agenda. Universities must step away from having an entitled attitude when dealing with industry and instead develop their value proposition. If you become known for offering value, you will be sought after by local institutions as well as international outfits. If we embrace highly specialised competencies in civil works and telecommunications, our students will be highly soft after and our school will be placed on a pedestal”.

“Being an African higher education institution today means an institution that is responsive to the challenges that the government, private sector, and society in general face. We have to take into account the trending issues around us. Issues like climate change, innovation, graduate employability, and value addition have to be high up our priority list. African higher education institutions have to advance the cause of development to the point that our governments no longer rely on foreign aid. We also have to equip the youth for the jobs of tomorrow, as well as encourage research. A research culture will set the stage for future high-level advancements originating from the continent. Our natural resource endowments also need to be exploited sustainably, and we have to drive that”.

Prof. Kenneth Matengu, Vice-Chancellor, University of Namibia. Namibia

“We want to change the way we practise agriculture. As a developing country, we have been taking care of our food needs through mostly subsistence farming. The use of rudimentary tools to plough the land has been the norm. We are confronted with the question of how much acreage of land can one plough with these tools to produce enough for the country. Mechanisation, therefore, has to be part of our agenda. We have to make the transition from H.T.T (How to Technology) to E.P.T (Engine Powered Technology). The adoption of technology and mechanisation will see us rapidly increase the acreage of our food production”.

“We want to change the way we practise agriculture. As a developing country, we have been taking care of our food needs through mostly subsistence farming. The use of rudimentary tools to plough the land has been the norm. We are confronted with the question of how much acreage of land can one plough with these tools to produce enough for the country. Mechanisation, therefore, has to be part of our agenda. We have to make the transition from H.T.T (How to Technology) to E.P.T (Engine Powered Technology). The adoption of technology and mechanisation will see us rapidly increase the acreage of our food production”.

Prof. Adeniyi Olayanju, Vice-Chancellor, Landmark University. Nigeria

“We have adopted very entrepreneurial programs that push students to not just train for already available jobs and existing businesses, but to also think of starting their own. All indications point to a future that is going to be very IT dominated and entrepreneurial. We, therefore, offer programs that have a business focus and in-depth knowledge of ICT. We are led by current market trends that define an excellent graduate as one that can invent, innovate and create. That market definition helps us shape our programs so that we put out graduates that are well equipped for the challenges out there”.

“We have adopted very entrepreneurial programs that push students to not just train for already available jobs and existing businesses, but to also think of starting their own. All indications point to a future that is going to be very IT dominated and entrepreneurial. We, therefore, offer programs that have a business focus and in-depth knowledge of ICT. We are led by current market trends that define an excellent graduate as one that can invent, innovate and create. That market definition helps us shape our programs so that we put out graduates that are well equipped for the challenges out there”.

Prof. Sulyman Age Abdulkareem, Vice-Chancellor, University of Ilorin. Nigeria

“There is a concern when it comes to the impact of research that comes out of our universities, and a need for change. In Kenya and I believe most of Africa, individuals move to the next grade in academia based on the number of publications they have produced. We want to change the focus from the number of publications to the impact of research made. The moment our research has a clear positive impact, we can now engage government and top industry players. Strathmore has become a reference centre for the Kenyan government on matters of renewable energy. We have also made a name for ourselves when it comes to public health. Our good fortunes are as a result of having some expert professors in our faculty who have made big names for themselves.

“There is a concern when it comes to the impact of research that comes out of our universities, and a need for change. In Kenya and I believe most of Africa, individuals move to the next grade in academia based on the number of publications they have produced. We want to change the focus from the number of publications to the impact of research made. The moment our research has a clear positive impact, we can now engage government and top industry players. Strathmore has become a reference centre for the Kenyan government on matters of renewable energy. We have also made a name for ourselves when it comes to public health. Our good fortunes are as a result of having some expert professors in our faculty who have made big names for themselves.

We have to move forward with the realization that the professors we have in Africa are not in any way inferior. Our collaborative model with institutions abroad is such that we get to exchange professors for a few lessons occasionally. Our inferences showed that our professors were just as good as those from Harvard and other top universities. There is, therefore, need to get our best educators, take care of them and depend on them. To have a successful future in research and education, our leaders must concentrate our creative and talented energies in Africa”.

Prof. John Odhiambo, Vice-Chancellor, Strathmore University. Kenya

“I want to leave this institution having encouraged all academic staff to make their mark in research. I also want to see researchers work in teams as opposed to individually as they have been doing for a long time. My vision is to have a quality research institution, and that is why we have procured quality equipment. We do not rest on our laurels waiting for government funding. We have gone even beyond our borders to seek financiers to help us keep our research agenda on track. Our Institute of Technology Innovation and Transfer (ITIT), is a stab towards the goal of being a research and innovation leader in the continent. We want our hub to have the same influence the Consortium for Affordable Medical Technologies (CAMTECH) has had. We want to have the same impact on education as CAMTECH has had in the medical field.”

Prof. Celestine Obua,Vice-Chancellor, Mbarara University of Science and Technology. Uganda

“I am passionate about education because I believe it is the only way we can develop as a society. I think that matters of science and technology are essential not just for industries but also for our political class. I would like our politicians to be in the know about science. In the future, I want the people we elect to be pulled from a much more diverse skillset so that we can be able to take the nation forward.

“I am passionate about education because I believe it is the only way we can develop as a society. I think that matters of science and technology are essential not just for industries but also for our political class. I would like our politicians to be in the know about science. In the future, I want the people we elect to be pulled from a much more diverse skillset so that we can be able to take the nation forward.

The literacy rates in the continent are not where they are supposed to be, and the scientific literacy rates are even worse. My vision is to make the University of Johannesburg a leader when it comes to the fourth industrial revolution competencies. I want to position it as a catalyst for the economic, social and political transformation of the African continent so that it can have a stake on the evolving global issues of our time”.

Prof Tshilidzi Marwala, Vice-Chancellor, University of Johannesburg. South Africa

“Tackling the world’s problems must involve educating people to the best of our ability as a society. Throughout time, the world has had to deal with three main problems; Ignorance, poverty and disunity. All communities and countries have the task of trying to deal with these problems while at the same realising sustainable human development. Related to the problems of ignorance, poverty and disunity; we can come up with goals that can help address them. Some of these goals include; sustainable human development, sustainable economic growth which should involve the fair distribution of income, as well as a higher standard of living; and the other goal is realising sustainable, peaceful coexistence”.

“Tackling the world’s problems must involve educating people to the best of our ability as a society. Throughout time, the world has had to deal with three main problems; Ignorance, poverty and disunity. All communities and countries have the task of trying to deal with these problems while at the same realising sustainable human development. Related to the problems of ignorance, poverty and disunity; we can come up with goals that can help address them. Some of these goals include; sustainable human development, sustainable economic growth which should involve the fair distribution of income, as well as a higher standard of living; and the other goal is realising sustainable, peaceful coexistence”.

Prof. Osman Nuri Aras, Vice-Chancellor, Nile University of Nigeria. Nigeria

“Improving our education system must start with analysing the regulatory regime in place; these regulatory regimes have guidelines that have been borrowed from the west. We must understand that this system was made to serve elites best, so we are leaving a lot of our people in the cold. The western model, however, gives a soft landing to the underserved in their society because they have the resources to support them; we in Africa don’t.

“Improving our education system must start with analysing the regulatory regime in place; these regulatory regimes have guidelines that have been borrowed from the west. We must understand that this system was made to serve elites best, so we are leaving a lot of our people in the cold. The western model, however, gives a soft landing to the underserved in their society because they have the resources to support them; we in Africa don’t.

We have to ask ourselves; are we reaching everyone? We also have to look at our vocational training. Is skill-based education present and where is it being taught? Skill-based education is very marginal in most places and almost regarded as separate from university education. It needs to be incorporated into campuses, and that’s when governments and other institutions will maximize the use of those institutions.

Africa churns out a lot of graduates, but industry does not think highly of most of them. Our role is to close the gap between what industry thinks is ideal and what we produce. As our economies continue to improve, we will see a higher placement percentage of our graduates in industry. At the moment our graduates are well sought after even in the more nascent economies. Our mission is to produce graduates that go on to build an independent and strong Africa”.

Mrs. Sheela Raja Ram, Vice-Chancellor, Botho University. Botswana

“African universities have been complaining for some time about how their research tended to be driven by research agendas from older and stronger institutions from outside Africa. Partnering with institutions outside Africa for research purposes was never a bad thing, the problem was that the research agenda was never defined by the African academic leadership.The keyword has to be relevance, with African universities. When you are linking teaching with research, you cannot forget the community development element aspect; which could be the immediate local community or the entire nation. The founders of this institution wanted it to be different from others of its kind in Nigeria and that is why internationalisation was made the main tenet of the university. The development of partnerships that looked inward instead of outward were also encouraged. Strong partnerships that looked inward helped this region add value to cassava which used to be simply a staple crop, and making it a major cash crop.

“African universities have been complaining for some time about how their research tended to be driven by research agendas from older and stronger institutions from outside Africa. Partnering with institutions outside Africa for research purposes was never a bad thing, the problem was that the research agenda was never defined by the African academic leadership.The keyword has to be relevance, with African universities. When you are linking teaching with research, you cannot forget the community development element aspect; which could be the immediate local community or the entire nation. The founders of this institution wanted it to be different from others of its kind in Nigeria and that is why internationalisation was made the main tenet of the university. The development of partnerships that looked inward instead of outward were also encouraged. Strong partnerships that looked inward helped this region add value to cassava which used to be simply a staple crop, and making it a major cash crop.

Nigeria is supposed to be the continent’s largest economy but her industrial base is still very weak compared to South Africa and even a smaller country like Kenya. Nigeria has a chance to rise up sharply because the federal government did well to set up parastatals dedicated to research. We have parastatals for doing research with regards to minerals and petroleum, another one for doing research when it comes to agricultural products and many others. Unfortunately, those institutions have underrated the research and development capacity they have possessed for so long, and their facilities have been underutilized. We were able to step in and add some value by collaborating with some of these institutions. Some of these facilities that had equipment lying idle are now functional. Our involvement in these parastatals is the first building block towards industrialization with the input of corporates”.

Prof. Kingston Nyamapfene, Vice-chancellor, University of Africa Toru Orua. Nigeria

“There often has been a challenge when it comes to the relationship between academia and industry. A lot of this has to do with independence in research. Research is crucial to academia for it provides information for training; the core business of universities. The industry thereafter utilises this research to come up with commercial products, processes and programmes to present to the general public. We are, therefore, often the originators of information that corporations use for innovation and commercialisation. The uneasy relationship between us and industry comes because the industry also does research. We must thus work together and ensure that the interests of commercialisation do not influence research output.

“There often has been a challenge when it comes to the relationship between academia and industry. A lot of this has to do with independence in research. Research is crucial to academia for it provides information for training; the core business of universities. The industry thereafter utilises this research to come up with commercial products, processes and programmes to present to the general public. We are, therefore, often the originators of information that corporations use for innovation and commercialisation. The uneasy relationship between us and industry comes because the industry also does research. We must thus work together and ensure that the interests of commercialisation do not influence research output.

At Amref International University, we believe in working with industry. Having decided to be a research university, our major programmes, revenue, and expenditure are research-oriented. We work with companies in the pharmaceutical industry in mutual but independent ways that provide value for vulnerable communities. Of particular interest are women, mothers and children in low and medium-income countries who are often vulnerable due to social, cultural and economic reasons. For example, Covid-19 has seen us work with various players to provide targeted and effective responses to the pandemic amidst economic challenges. We appreciate that companies are right to patent their intellectual property, but it is, however, important to consider ethics. Is it ethical for antiretroviral drugs, for instance, to become unaffordable and inaccessible to the poor who are most vulnerable? Working with industry players is, therefore, a balance between recovery of research and development costs without neglecting communities.

Our main focus is Africa, but we recognise that we are one large interlinked global community. This is particularly evident in health where due to increased efficient travel; a local problem can soon be a global health challenge. We also recognise that a lot of industry players in the continent are domiciled in other places. We have thus partnered with some of these companies where their corporate social responsibility funds are remitted to the research cause of the countries they operate in. AMREF thus uses the resources generated in a country for health research within the same country, thus inspiring lasting change”.

Prof. Marion Mutugi, Vice-chancellor, Amref University. Kenya

“Research and development are absolutely vital to the development of this continent. We shouldn’t be in the position we are in as a continent with abundant natural and human resources. As academics, we look to attack the problem through impactful research. Just last week, my staff and I heard from my mentor, who is the Vice-Chancellor at the University of Ibadan. We held an impactful educational session on how to attract research grants. Our institution has a strong focus on research because we know what original local research can do for our communities. We know that our efforts will lead to positive developments that will be award-worthy in the future.

“Research and development are absolutely vital to the development of this continent. We shouldn’t be in the position we are in as a continent with abundant natural and human resources. As academics, we look to attack the problem through impactful research. Just last week, my staff and I heard from my mentor, who is the Vice-Chancellor at the University of Ibadan. We held an impactful educational session on how to attract research grants. Our institution has a strong focus on research because we know what original local research can do for our communities. We know that our efforts will lead to positive developments that will be award-worthy in the future.

Internationalisation is a massive part of our agenda. We have made efforts to collaborate with universities far and wide, while also accepting students from outside Nigeria. Ours is a diverse university with students from Togo, Benin, Cameroon and other countries. We believe in forming strong partnerships with other universities within the continent first before looking abroad. A broad network within Africa will enable some of our PhD students, for instance, to gain experience outside Nigeria. All these efforts are geared at making our university a truly international one”.

Professor Noah Yusuf B.Sc (Hons.), Vice-chancellor, Al-Hikmah University. Nigeria

“Education is a key in our developmental goals and I commend the government for having a firm focus on education. I would urge all stakeholders in the private and public sector to put in more resources into research. Our research and development has to be tailored to specific environments. We must ask ourselves what our challenges are, how we should address them, and what role education plays in all of this. Even more important is the question of whether relevant stakeholders are properly harnessing the knowledge of educators.

“Education is a key in our developmental goals and I commend the government for having a firm focus on education. I would urge all stakeholders in the private and public sector to put in more resources into research. Our research and development has to be tailored to specific environments. We must ask ourselves what our challenges are, how we should address them, and what role education plays in all of this. Even more important is the question of whether relevant stakeholders are properly harnessing the knowledge of educators.

Proper resourcing and communication will improve the entire ecosystem. The industry will look to educators for skills and talents, and educators will look at government and industry for enabling resources as well as policy. Before such an ecosystem can be successfully put up, we must structure education well at the basic level. If the superstructure at the top is not built on a firm foundation, the whole thing will come down”.

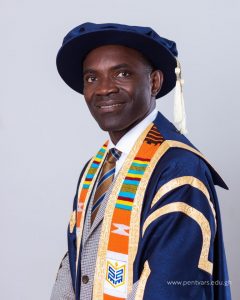

Dr. Daniel Okyere Walker, Vice-Chancellor, Pentecost University College. Ghana

“There is an argument to be made that historically much of the policy based discussions on science, technology and innovation have, understandably, leaned heavily on the relationship between academia, business and industry. These discussions, however, have to some extent ignored the impact that academic research may have on social innovation. A result of this is that social and environmental goals are often inadequately covered in African science, technology and innovation policy frameworks. This is significant because a lot of the money now coming to the continent from development agencies, through a variety of programmes, is directed towards social innovation and entrepreneurship and associated impact. There is need for more research to accompany these programmes to advise on how they may be directed to maximise social and environmental goals, as well as economic goals.

“There is an argument to be made that historically much of the policy based discussions on science, technology and innovation have, understandably, leaned heavily on the relationship between academia, business and industry. These discussions, however, have to some extent ignored the impact that academic research may have on social innovation. A result of this is that social and environmental goals are often inadequately covered in African science, technology and innovation policy frameworks. This is significant because a lot of the money now coming to the continent from development agencies, through a variety of programmes, is directed towards social innovation and entrepreneurship and associated impact. There is need for more research to accompany these programmes to advise on how they may be directed to maximise social and environmental goals, as well as economic goals.

Malawi’s academic and business communities are relatively small and there is an opportunity to improve the dialogue between them. Malawi has recently established a National Planning Commission which is now enabling discussions amongst different sectors to take place more easily. Given appropriate strategic leadership, these discussions can hopefully lead to policies and plans that yield economic growth combined with a positive social and environmental impact”.

Dr. Robert Ridley, Vice-Chancellor, UNICAF University. Malawi

“Institutions like ours can only operate optimally if the right connectivity infrastructure is laid out. We liaised with Eswatini Postal Services to set up delivery linkages while also setting up partnerships with major telecommunication companies like MTN, to help us get strong internet connections for us to work remotely. That firm groundwork has led to us having solid communication infrastructure that enables us to offer virtual classes, something that seemed impossible only five years ago.

“Institutions like ours can only operate optimally if the right connectivity infrastructure is laid out. We liaised with Eswatini Postal Services to set up delivery linkages while also setting up partnerships with major telecommunication companies like MTN, to help us get strong internet connections for us to work remotely. That firm groundwork has led to us having solid communication infrastructure that enables us to offer virtual classes, something that seemed impossible only five years ago.

As we seek to improve our economies, all stakeholders must be cautioned against the silo mentality. We must devise ways to create better links and open lines of communication that will help get things moving. Once we overcome our communication challenges, we can grow together sustainably. At times, you may be stuck with a problem, yet the answers lie in a nearby institution that you don’t know of. Clear channels of communication will help us source answers from within the continent”.

Prof. Winnie Nhlengethwa,Vice-Chancellor, Southern Africa Nazarene University. Eswatini

“The government is increasingly realising the value of skill-based development. This is why institutions like ours are getting a bit more attention compared to previous years and decades. Students, who are well-read on theory but cannot do anything with their hands, aren’t going to benefit this economy much. The government has, therefore, asked all technical universities to identify their niche areas and equip students accordingly.

“The government is increasingly realising the value of skill-based development. This is why institutions like ours are getting a bit more attention compared to previous years and decades. Students, who are well-read on theory but cannot do anything with their hands, aren’t going to benefit this economy much. The government has, therefore, asked all technical universities to identify their niche areas and equip students accordingly.

Our niche is electrical and electronics engineering and we are going to impart related skills on students to help power Ghana’s development agenda. We are into electric vehicle technologies research and we wish to be the institution that plays the biggest role in making Ghana become a big part of the electric vehicle manufacturing countries across the globe by 2030.

Our country and continent has changed a lot in terms of education. In the early years just after independence, we had to send our people to America, Asia or Europe for specialised training. Our universities have stepped up and now the number of students going abroad for education has reduced significantly. The COVID 19 pandemic has dampened the momentum we had but despite that, we are slowly sorting out and developing our virtual learning capabilities. A post-COVID-19 world will see us develop our ICT infrastructure because it’s now clear why this must be done urgently. Developing the ICT infrastructure will depend on workable synergies between the industry and government”.

Prof. Adinkrah Appiah, Vice-Chancellor, Sunyani Technical University. Ghana

“Our relationship with the industry really depends on the sector. Our university has great relationships with the medical, legal and ICT sectors. A good number of professors and well-respected professionals have come from our institution. We are, however, struggling in areas like agriculture because we have had professors in that area who don’t practice.

“Our relationship with the industry really depends on the sector. Our university has great relationships with the medical, legal and ICT sectors. A good number of professors and well-respected professionals have come from our institution. We are, however, struggling in areas like agriculture because we have had professors in that area who don’t practice.

Students have to relate to what is being presented on PowerPoint with real-life examples. We are working to change that so that our agriculture students can have a better educational experience.

The funding model for our universities has been flawed for a long time. We need to be financed not only based on the number of students we admit. Factors like teaching and research must also be considered. Funding must be targeted towards research because that’s how we get the data we need to solve the housing crisis, food insecurity and other issues that plague our economy. Our role can be more than just providing personnel, we can do much more if the funding we need is provided”.

Prof. Stephen Kiama, Vice-Chancellor, University of Nairobi. Kenya

“There is a lot of blame game between academia, and the industry. We should get past the disagreements and work together for the good of the collective. The industry in our country is still at its formative stage and they seem to not see much need in our involvement in their activities.

“There is a lot of blame game between academia, and the industry. We should get past the disagreements and work together for the good of the collective. The industry in our country is still at its formative stage and they seem to not see much need in our involvement in their activities.

We have taken a proactive approach by organising a partners meeting every year where we showcase our projects. Instead of waiting for the industry to come to us, we decided to bring them in to try and spark an interest. Our efforts are beginning to reap rewards and both parties are increasingly seeing the need for partnership.

We have a population bulge right now of young people that need quality education. Our challenge is to develop the capacity to meet the demand. Our economies must also be vibrant enough to absorb the thousands of fresh graduates that come out every year. Special emphasis must be paid to TVET programmes so that our youth can have the opportunity to create opportunities in their own way. A focus on the environment is a must because all our other efforts will be in vain if we lack natural sustainability”.

Prof. Doutor Orlando António Quilambo, Rector, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane. Mozambique

“We have to ensure that we stay update to not only the needs but the new developments out there. It is also imperative for us to look into the future to see how best we can prepare. I took some time to look at our graduate programmes and compared them to those in international markets. I also took some time to analyse the skill level and work ethic in various markets compared to ours. My analysis has me convinced me that we must fix our issues by redoing our whole education system. We must turn to problem-solving oriented education so that we can service the needs of all stakeholders in our societies.

“We have to ensure that we stay update to not only the needs but the new developments out there. It is also imperative for us to look into the future to see how best we can prepare. I took some time to look at our graduate programmes and compared them to those in international markets. I also took some time to analyse the skill level and work ethic in various markets compared to ours. My analysis has me convinced me that we must fix our issues by redoing our whole education system. We must turn to problem-solving oriented education so that we can service the needs of all stakeholders in our societies.

Graduates shouldn’t have to seek additional skills so that they can be useful to the job market. Precious productive years are lost when graduates have to be retrained because universities didn’t do a good enough job. The way around this is to ensure that the time spent by students in the university is worthwhile and that they are ready to offer value immediately after graduation. Our institution, therefore, invites business leaders and other industry captains to give input on what we teach, while also advising on the mode of delivery. Collaboration will also help universities get better. If schools from different parts of the continent communicate, then skills can be shared and our students can all benefit”.

Reverend Professor Kwabena Agyapong-Kodua, Vice-chancellor, Pentecost University