by Jim Tan on 20 July 2021

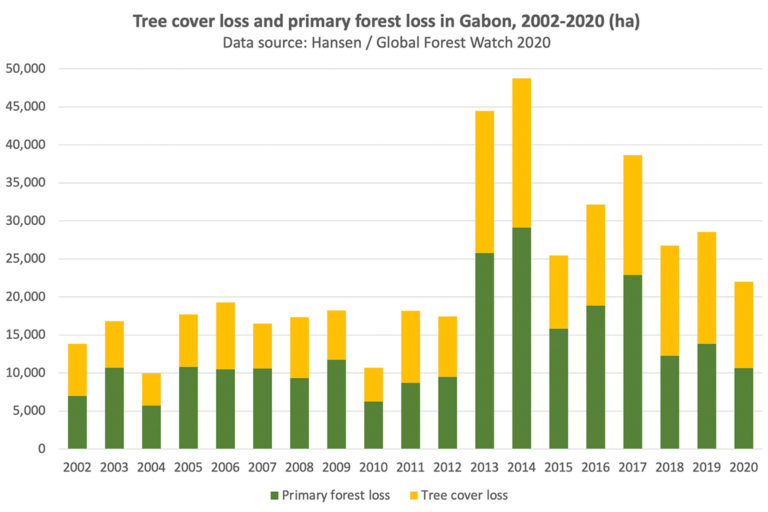

In 2019, Norway committed to pay $150 million to Gabon to protect its forests under the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI). After independent verification of the country’s deforestation rates in 2016 and 2017, Gabon recently received its first $17 million payment, making it the first African country to receive a results-based payment for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+).

“I think it’s good news,” said Denis Sonwa, senior scientist for the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Cameroon. “It shows that REDD+ is technically possible, but for it to become a reality we need some sort of dynamic domestic policy.”

CAFI was founded in 2015 as a collaborative agreement between six central African countries — the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon — and six financial partners: the European Union, France, Norway, Germany, South Korea and the Netherlands.

CAFI is based around the REDD+ mechanism developed by the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The idea that underpins REDD+ is that developing nations should be able to financially benefit from the ecosystem services that their forests provide, such as carbon storage and as reservoirs of biodiversity. The REDD+ concept has been around since 2005 and trialed in various forms, with varying degrees of success.

With 88% of the country covered in tropical rainforest and an average deforestation rate of less than 0.1% over the last 30 years, Gabon is what’s known as a high-forest, low-deforestation (HFLD) country — one of only 11 in the world to claim this status. The forests of Gabon have immense biodiversity, with more plant species than all West Africa’s forests combined. Gabon is also one of the few places left in the world where forest elephants can roam all the way from forest to sea and can be found sauntering along the beach.

“In terms of carbon emissions, we were actually positive,” Lee White, Gabon’s minister of forests, oceans, environment and climate change, said in a BBC interview. “We absorb 100 million tons of carbon dioxide over and above our annual emissions.”

Gabon’s situation is unusual. Discovery of oil in the 1970s radically changed the country’s fortunes and the dynamics of its society. In 1970, urbanization in Gabon was 30%; by 2020, more than 90% of Gabon’s population lived in urban areas, compared to a sub-Saharan Africa average of 41%. Gabon also has a very low population density, with just eight people per square kilometer (about 21 per square mile) compared to the average of 45 per km2 (117 per mi2) for sub-Saharan Africa.

This rare combination — low population and high urbanization, supported by oil revenue — has limited the human impact on Gabon’s forests. Oil has been the foundation of Gabon’s economy, accounting for 80% of exports and 45% of GDP between 2010 and 2015. However, oil reserves are now running low, and with oil prices unstable, Gabon’s government is looking for new ways to power its economy.

With limited agricultural land available, Gabon has to import food — $591 million worth in 2018 alone. The country wants to generate more income from its forests as well as preserve them, and CAFI is one part of that plan.

“We’re trying to come up with a new development model for a high rainforest country that preserves the forest but allows us to develop,” White said.

To be financially as well as ecologically sustainable, the timber industry needs to make and retain as much value as possible in-country. Since 2010, Gabon has only allowed timber to be exported once it has been processed to some degree. Gabon has also adopted a sustainable approach to forestry to minimize degradation, with timber companies required to harvest on a 25-year cycle to allow regrowth. In 2018, President Ali Bongo also declared that all forestry concessions must be FSC-certified by the end of 2022.

Recognizing that Gabon’s deforestation rate is already low, CAFI’s payments to Gabon focus on reducing CO2 emissions from degradation through sustainable forestry practices. CAFI will also pay for the CO2 Gabon’s natural forests sequester, hoping to give the forests value as they stand, beyond timber. The money received from Norway will be put toward further developing Gabon’s sustainable forest model.

With oil exports of $4.7 billion in 2019, Gabon faces an uphill struggle to replace oil revenues in a sustainable manner. As well as sustainable forestry, oil palm has featured prominently on Gabon’s diversification agenda, raising concerns over potential forest conversion.

It’s still early days for CAFI’s other initiatives. CAFI committed to investing $200 million into programs designed to address deforestation in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2016. Since the deal was signed, instability in the country has hampered CAFI’s efforts, and the discovery of oil beneath the peatlands of the Cuvette Central have raised concerns about the effectiveness of any deals signed. CAFI has not yet made any significant commitments to the other four partner countries.

It remains to be seen if the other countries can emulate Gabon’s success in achieving results-based payments for protecting their natural forests or whether Gabon can diversify away from oil while keeping its forests intact.

What is undeniable is the value of the Congo Basin and the global consequences if countries like Gabon cannot find a way to achieve the development they need without sacrificing their rainforest.

“The Gabonese and Congolese forests help to create the rainfall in the Sahel, so if we lose the Congo Basin we lose rainfall across Africa,” White said. “If we lose the carbon stocks in the Congo Basin, which represent about 10 years of global emissions of CO2, we lose the fight against climate change.”