Bradley Hiller, Anglia Ruskin University

African leaders have joined a worldwide thrust for a “green recovery” from the COVID-19 setback and the climate crisis. As the African Union’s Green Recovery Action Plan puts it, this essentially means investing in the sustainable use of resources. A joint statement endorsed by 54 African leaders emphasises the continent’s need to develop “based on a deep understanding of climate risks”.

Research suggests that such green recovery strategies – especially in agriculture and food security – could draw on a relatively under-developed resource: groundwater.

Groundwater is water under the surface of the ground, typically accessible via wells and boreholes. It’s not visible like a great river. This can be beneficial because groundwater is less exposed to evaporation and surface pollution.

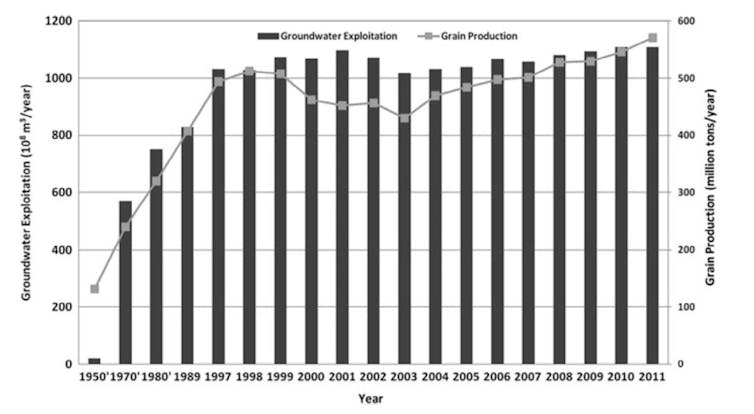

Groundwater has supported impressive spurts of development in some parts of the world. California’s irrigation and industrial boom, India’s green revolution, and China’s national grain production increase are examples.

Jie Liu and Chunmiao Zheng

But in sub-Saharan Africa, groundwater doesn’t get such attention. Rather, regional water resource management focuses on surface water development. The Nile Basin Initiative and the Zambezi River Authority are two such examples. There aren’t any high-profile groundwater authorities.

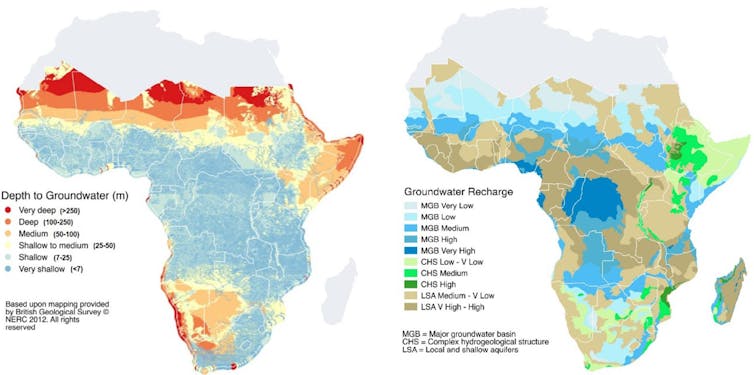

Knowledge about groundwater is scarce in some countries. Development tends to be informal and limited to shallow use. This contributes to the belief that groundwater resources in sub-Saharan Africa aren’t large enough, or conveniently located, to significantly contribute to socioeconomic development.

But our synthesis of regional findings suggests otherwise.

Combining data on the physical availability of groundwater with information on political-economy factors, our study revealed that groundwater is by far the largest regional water resource by volume. Annual renewable groundwater in the region is equivalent to 15 years of average total flow of the Nile River. We also found that renewable groundwater is often available where it’s most needed and at depths of less than 100 metres.

Strikingly, we found that less than 5% of the region’s renewable groundwater is being used. Its potential for sustainable use is tremendous.

a) Alan Mackenzie Macdonald et al. 2012. b) Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (Germany) and UNESCO 2008.

Various studies also support our technical findings. A recent study found opportunities for sustainably withdrawing groundwater across much of the continent. In short, there’s an opportunity for a renewed regional focus on sustainable groundwater development.

Potential impacts of groundwater

Our findings suggest that groundwater could support critical sectors across the region.

- For example, it could help increase sub-Saharan Africa’s current irrigated land area, which is currently 3%.

- Groundwater could increase per capita water consumption, currently the lowest globally.

- It could help cities guard against shocks such as the “Day Zero” water crisis in Cape Town, South Africa. And it could lessen the impacts of recurrent droughts.

Stronger regional water and food security could support poverty reduction, economic structural change and a transition to higher value-added activities. Ultimately, these could contribute to greater regional prosperity.

Preliminary results from an economic simulation in Uganda, for example, found that doubling investment in sustainable groundwater development could increase agricultural GDP by 7%, create 600,000 jobs, and alleviate poverty for half a million people nationally by 2030.

Political economy factors

There is evidence that macro policy support in China, New Deal infrastructure in the US, and electricity pricing policy in India all helped kickstart larger-scale groundwater development.

Understanding political economy factors in sub-Saharan Africa is vital to unlocking the potential benefits of groundwater development and managing trade-offs. Such factors include land rights and tenure, energy availability and price, access to credit, and the cost and availability of drilling equipment and pumps, amongst others.

There are already examples of how innovation and leadership in the region can unlock this potential. A managed aquifer recharge scheme in Windhoek, Namibia – the driest capital in the region – is an engineering and financial success for city water supply. The scheme also preserves the fragile Okavango River.

The cost of technologies such as renewable energy and desalination is falling. They offer further possibilities, coupled with approaches such as farmer-led irrigation development and improved end-use efficiency measures.

Kick-starting green recovery

Groundwater has the potential to support broad economic, humanitarian and social development in sub-Saharan Africa. It has done so in other regions globally. But resource development must be sustainably managed.

There’s no denying the potential for pitfalls. For example, over-exploitation of groundwater in some parts of California has led to water stress and land subsidence. Consolidating such international lessons with recent regional experiences could inform sustainable groundwater governance in sub-Saharan Africa from the outset.

As a starting point, a framework for action could include raising the profile of sustainable groundwater development potential in the region. The emphasis should be on ecosystem health and empowering vulnerable communities.

The year 2022 presents promising opportunities. In February, addressing the African Union, the UN Secretary General highlighted the importance of green recovery to ignite economic recovery. The African Union’s theme of 2022 focuses on transforming food and agricultural systems. Groundwater, which is the theme of World Water Day 2022, can help respond to such calls to action.

Jude Cobbing, Advisor: Water Governance and Infrastructure at Save the Children US, also contributed to this article and the research it’s based on.![]()

Bradley Hiller, Former AsiaGlobal Fellow, Asia Global Institute, University of Hong Kong. Former Visiting Fellow, Global Sustainability Institute, UK., Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.