Noam Angrist, University of Oxford

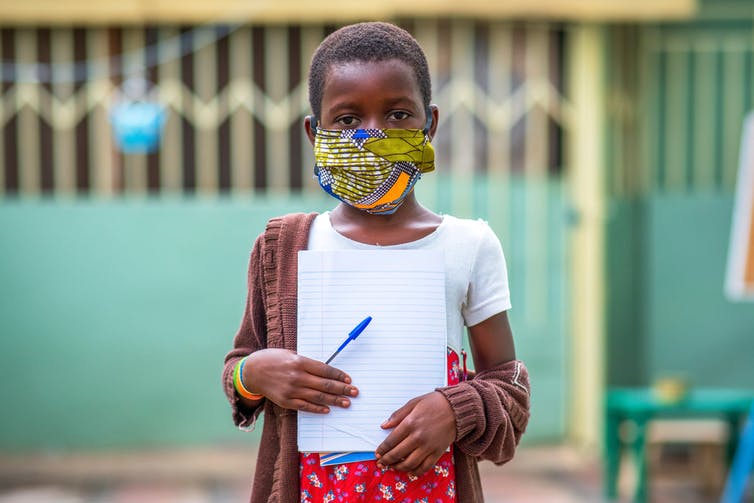

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a historic shock to education, shuttering schools for over 1.6 billion children worldwide. This shock will worsen a pre-existing “learning crisis” in which many students in school were learning very little. The World Bank estimates that the percentage of children who are unable to read a simple sentence by age 10 could rise from 53% before the pandemic to 63% as a result of school closures.

These learning losses could stem from a combination of things: forgetting what was previously known, and missing what would have been learned if schools hadn’t been closed. These learning losses can accumulate in the long run. Students who re-enter school far behind the curriculum expectations might be too far behind to learn anything from daily instruction and fall even further behind.

In a new paper, we looked at how much learning loss might be experienced in Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Tanzania and Uganda as a result of school closures in the pandemic. We used data from early grade reading assessments in these countries. Our model suggests there could be up to a year’s worth of learning loss in the short run. Our estimates suggest learning losses will be distributed unequally, with students who started at lower learning levels falling the farthest behind.

We estimate that these short-term learning deficits could accumulate to 2.8 years of lost learning in the long run. This is if the curriculum – often overambitious and not aligned to students’ learning levels – is not adjusted to allow students to catch up.

Opportunity for reform

But that doesn’t have to be the outcome.

While COVID-19 has held back learning, bold reform is possible and the pandemic presents a historic opportunity to revamp education systems. It could be a time to institute practices and policies that have been needed to address the underlying learning crisis for decades.

Our review of the literature identified two strategies which could help to mitigate learning losses and improve learning even beyond pre-COVID-19 levels. This review builds on a growing evidence base of interventions that have worked at scale in low- and middle-income countries to improve basic numeracy and literacy skills.

The first strategy is to target instruction to a child’s learning level. This can be achieved at little cost by testing the child’s knowledge during the learning process – known as formative assessment – and a menu of activities tailored to each child’s level. This has more potential than teaching prescriptive one-size-fits-all syllabi.

The second strategy is to introduce structured pedagogy programmes, which combine structured lesson plans, teacher coaching and instructional support. Many teachers in the status quo are often left to fend for themselves and write their own daily lesson plans. By providing some structure and ongoing support, big learning gains are possible.

Both approaches in past reviews have been found to improve learning by three years of high-quality schooling gained per US$100. These learning gains are nearly equivalent to the system-level education gap between Zambia, one of the lowest performers in sub-Saharan Africa, and Kenya, one of the highest performers.

Our model suggests that short-term remediation through these strategies can make a sizeable dent on learning losses. More strikingly, ambitious reforms linked to these strategies, such as aligning instruction with children’s learning levels on a long-term basis, can not only mitigate all learning losses, but also improve on pre-COVID-19 learning levels.

Signs of progress

In our study we describe a few examples of countries which are starting to enact such reforms, including Botswana and Madagascar. In Botswana’s second largest region, the North-East, the Ministry of Basic Education’s regional director called for all schools to conduct simple formative assessments and implement targeted instruction immediately as schools reopened in June 2020 following the first wave of COVID-19 induced school closures.

The region updated staff’s roles and responsibilities to formalise this expectation. Training sessions were held with support from one of the largest youth-serving NGOs in the country, Young 1ove, in partnership with USAID and UNICEF. The ministry expected frequent reporting on progress, and the regional director visited schools directly to monitor implementation. Although no causal evidence is available yet, early data suggest learning levels are improving faster than in other regions.

Madagascar provides another example. The government has strengthened the national catch-up programme, called CRAN, which prior to the pandemic had been providing a two-month intensive learning period to children targeted to their level. By the end of 2018, CRAN had been implemented with UNICEF support in seven out of 22 regions of Madagascar. In late 2020, in response to COVID-19 school closures, this approach was accelerated. Although the government and UNICEF are in the early stages of this work, it shows how governments can strengthen existing programmes to shift teaching and learning practices.

These reform efforts are promising. Yet, too few countries have taken bold steps to date. Without urgent action, short-term learning losses could stunt the next generation of students for a lifetime, with potential inter-generational consequences. COVID-19 presents a need to act urgently and an opportunity to think differently. Perhaps some education systems will reform to achieve the long sought-after goal of learning for all.![]()

Noam Angrist, Executive Director, Young 1ove, Fellow, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.