Hundreds of years ago, Mbenje Island was home to a proud and permanent population. Living in houses made of grass and sticks, the community lived comfortably on this mountainous piece of land in the middle of Lake Malawi, travelling to and from the mainland to trade.

The people came to believe, however, that this was no ordinary place. Men would report meeting apparitions, including of naked women, while on fishing expeditions. Others noticed that whenever someone killed a snake, which are endemic on island, violent storms would soon follow. To calm the spirits and bring peace, the island’s chiefs started offering sacrifices and initiating new traditions.

Since those days, many things have changed. For instance, today’s descendants of Mbenje’s settlers mostly live in Chikombe, a thriving business centre across the lake in mainland Malawi. But many other things have stayed remarkably consistent. While over-fishing and the climate crisis have contributed to dwindling catches elsewhere in Lake Malawi, the waters around Mbenje remain abundant with fish – something many attribute to the maintenance of the traditions established long ago and handed down generation to generation ever since.

Fixing boats on Chikombe beach before the journey. Credit: Charles Pensulo.

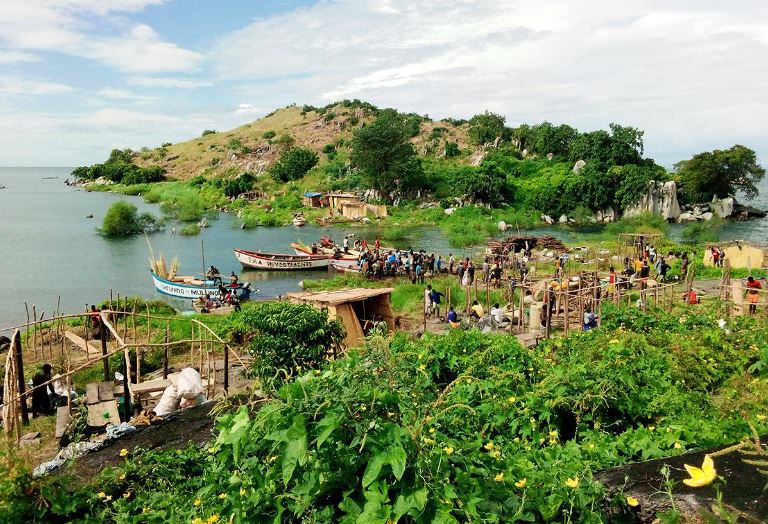

On the first Saturday morning of April, dozens of men and boys are gathered along the shores of the lake at Chikombe beach. Most are busy repairing their boats or patching up fishing nets. Piles of their belongings, including tools they’ll use to build makeshift houses, sit nearby. This is the day they have been waiting for. In accordance with ancient rules, Mbenje Island is strictly off-limits from December to April. Today is the day of return.

For the next eight months, the island will become home for these fishermen. There may be occasional trips to the mainland to fill up on supplies, but for the most part, Mbenje will go from being empty to hosting a self-sufficient community. Businesses selling food, clothes and other goods will accompany the travellers. Even refrigerators stocked with cold drinks and video showrooms will be established to keep the men entertained.

The fishermen will, however, have to follow some strict rules. As is custom, Muhammad Magwere explains these instructions to those gathered on the beach before they embark on the one-and-a-half-hour trip to Mbenje. The 50-year-old is the Senior Chief Makanjila, keeper of the tradition, and a messenger for the gods. It was Magwere that set the specific date for the re-opening in consultation with spirits and recent weather patterns. He also oversees today’s ceremonies.

Earlier, he delegated trusted assistants to offer sacrifices to the island’s spirits. Now, flanked by aides and officials from the Fisheries Department and district council, he addresses the crowd. On the island, he tells them, animals and colourful birds coexist with the people. It is prohibited to kill any wildlife, including snakes. Stealing, drinking alcohol and smoking are also punishable by banishment for the rest of the fishing season. And, no women are allowed.

These rules have shaped the community’s stewardship of the local ecosystem for centuries. As Magwere tells African Arguments, “we believe that God first created the animals and plants, and then created a man to look after them. We believe that those who don’t take care of the wildlife will be answerable before the creator.”

“All these rules were passed down from our ancestors and any diversion is met with calamity,” he says. “We have ten islands in the lake, but I can proudly say it’s ours that has a good catch of fish and people travel from elsewhere in the country to benefit from us.”

This sentiment is echoed by Malawian officials who describe Mbenje as iconic. The government has begun supporting and even trying to emulate its practices elsewhere.

“What is being done here is participatory fisheries management,” says Kingsley Kamtambe, Fisheries Researcher at the Ministry of Agriculture. “[It] is something we would like to do and implement in most of the fishing districts in Malawi.”

The official praises the community’s policing of illegal fishing and its tradition of closing completely for four months of the year. By contrast, he says, other areas only restrict fishing with bigger nets for two months.

“I have never seen data comparing Mbenje and other places when it comes to fish catches. But what we know is that when we open up Mbenje, they catch a lot of fish,” says Kamtambe.

On the boat to Mbenje Island. Credit: Charles Pensulo.

On board a boat inscribed with the words Chifundo cha Mulungu (“God’s grace”), there are about thirty fishermen with their belongings. As they make the journey to the island, they speak in a whole range of dialects and languages. Anyone can fish on Mbenje once approved by a committee, and men come from far and wide to take advantage of its abundant waters.

Wilimoti George, 30, travelled from Nsundwe in the capital Lilongwe to smoke and package fish on the island. He wants to raise the money to start a farming business back home and believes he’ll have enough by the end of the season.

“The good thing is that there is no alcohol and women so I will be able to save the money,” he says. “The culture at the island is important because you help one another and live as one family. You don’t have that back there.”

Asmen Kamanga, 33, journeyed over 150km from Karonga district after first hearing about Mbenje from other fishermen. He has worked on the island in previous seasons and hopes to use his earnings this time to pay school fees for his children and siblings and support his family. Despite being away for most of the year, he says he doesn’t miss home as amenities on Mbenje such as makeshift videorooms keep him entertained.

“If there is an island in the country that we depend on and where we get money, it is this island,” he says. “Life here is very good and we just go [back] to the shore because of the laws. On this land, there are no fights, alcohol and things that waste money. By the end of season, we make up to a million kwacha [$1,250] since we are small fishermen, but the bigger fishermen make millions.”

Barabado Yahaya, a committee member who supervises the fishermen on Mbenje, echoes these claims. He says that over 6,000 fishermen live on the island every year and that in a good season, fishing crews can make millions of kwacha each week.

“This island has helped us to educate children, raise orphans, own property and build beautiful houses,” he says.

Of course, not all Malawians are able to reap the full benefits of Mbenje. The ban on women means the island is permanently off limits to half the country’s population. Some see this as discriminatory. But others like Esnart Shaibu, 35, support the system. She runs a clothing business in Chikombe, which is thriving thanks to the fishing industry. She says she is content with the prohibition given it was informed by the spirits and that women profit indirectly.

“We do benefit from the island in many ways, not least because our husbands and children fish on the island,” she says. “Business booms during the fishing season and money circulates in the area. You don’t have to be at the island to actually benefit.”

If the Malawi fisheries department can successfully emulate Mbenje’s traditional practices that have protected the environment for centuries as unsustainable fishing practices and climate change have created crises elsewhere, it is possible that many more could benefit from the island’s example too.