South Africa’s freshwater sources are under pressure from various kinds of contaminants, and NWU researchers are searching for ways to keep track of some of the more elusive pollutants.

Prof Rialet Pieters, a researcher in the Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, is an ecotoxicologist whose interests lie in organic chemical pollutants and their harmful effects on humans and wildlife.

Studies have determined that the quality of available freshwater is declining rapidly because of changing weather patterns, as well as human-related activity.

Wastewater treatment plants do not do an effective job of removing pollutants such as pesticides, personal care products and pharmaceuticals which ultimately end up in water sources and further

impact the already dire levels of the availability of freshwater.

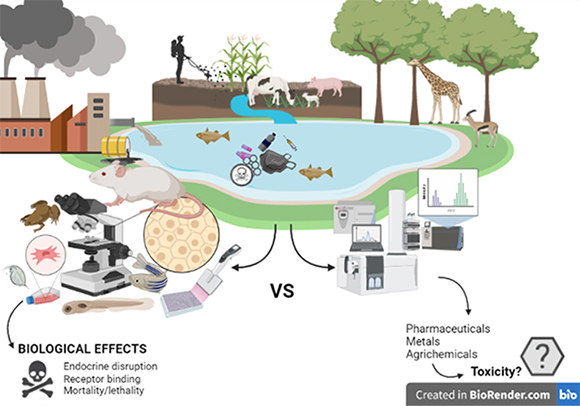

Prof Pieters and fellow researchers are hard at work finding solutions to improve the monitoring of our freshwater sources. They use methods collectively called bioassays, which are analytical methods used to determine the potency of a substance or mixture of substances by its effect on life.

These effects could be in vivo, referring to the impact on living animals or plants, or in vitro, meaning living cells or tissues. A bioassay can be either qualitative or quantitative, direct or indirect.

What bioassays do

Bioassays are an effective tool to use, she says, because they indicate how the chemical mixtures in the water would influence animal and human health. “Combining the chemical and biological analyses will provide results of the active chemicals present in the sample, as well as the joint biological effect caused by the chemical mixture.”

Prof Pieters says, “Organisms commonly used for in vivo assays include algae, daphnids, frogs and fish. In vitro assays, which are mostly cell-based although they also include bacteria and yeast, are used as a first-tier screening tool and reduce the use of whole organisms.” Worldwide in vivo and in vitro bioassays are increasingly used to determine water quality.

Shortcomings of the usual approaches

Traditionally, water quality is determined by measuring the concentrations of a few pre-selected compounds through chemical analyses, says Prof Pieters. Comparing concentrations to a maximum permitted value according to a standardised guideline is commonly used to assess the quality of water.

Unfortunately, she adds this approach does not consider the effect of chemical mixtures. Chemical analysis also overlooks unknown chemicals and transformation products. “In addition, no chemical analysis can report the biological effects of a chemical cocktail on plant and animal life in an ecosystem, regardless of the list of compounds. When monitoring the quality of drinking water and environmental water, biological analysis is crucial,” she says.

Why water quality is declining

Despite legislation and guidelines set in place in South Africa to protect, manage and provide good quality water to citizens, several factors such as mismanagement, failed infrastructure, lack of expertise and financial issues add to the rapid decline in safe water quality. Although the Department of Water and Sanitation implemented the Blue and Green Drop programmes in 2009 to ensure better drinking water quality and wastewater treatment, the programmes were discontinued only five years after they were initiated.

This is just one example of monitoring programmes that have stalled, while others never got off the ground.

The country has the research capacity to assess the toxicity of pollutants at various trophic levels, which is important because sensitivity to pollutants varies between species and trophic levels in food chains, says Prof Pieters. However, this is not done by governmental monitoring laboratories.

South African research laboratories are able to test the quality of water using a wide variety of biological endpoints including lethality, swimming behaviours, hatching rates and germination rates. There is also the ability to evaluate the water quality via reporter gene assays by looking at endocrine disruption and dioxin-like activity but is not incorporated into current national ways of determining water quality. Even though bioassays are envisaged to provide a holistic overview of the water quality in South Africa, they will not improve the failing sanitation and water distribution infrastructure.

As with any solution, it must be holistic. Bioassay monitoring, combined with investments in infrastructure and proper maintenance, could be the answer.