Khato Civils CEO Mongezi Mnyani has called on financiers and governments to ensure that African infrastructure is primarily built by African firms. The call comes as concerns grow over the lack of local participation and consultation in the continent’s infrastructure rollout.

Mr Mnyani has spoken out to highlight the damage created by failing to engage with local communities and enterprises when funding and developing infrastructure projects.

The South African based CEO has called for a change in approach from development finance institutions including The World Bank and The African Development Bank. Investments from such institutions are structured in a manner that often locks out local firms.

Mr Mnyani also criticised the local content policies in place in many African countries as a “box-ticking exercise”, calling for change across government and industry to ensure truly inclusive economic growth in Africa’s major economies.

In an interview with AfricaLive.net, Mr Mnyani highlighted Khato Civil’s recent 100km pipeline project in Botswana as an example of local firms creating economic and social impact through infrastructure build.

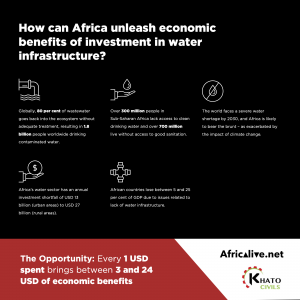

Mr Mnyani has outlined 5 threats to African development from the exclusion of local businesses and communities in infrastructure projects:

Economic Threat – The economic threat to society comes from a failure to foster local entrepreneurship through a lack of economic benefits reaching local businesses and skilled workers. There is also a financial penalty for clients and project developers to pay as projects are disrupted and delivered late & over budget.

Threat of Instability – Projects that fail to create employment and subcontracting and supplier opportunities are at risk of protests, disruption and sabotage from those excluded communities. At a wider societal level, the recent points of conflict in South Africa demonstrate how anger at exclusion from economic development can destabilise and disrupt entire nations.

Social Threat – The social threat comes from the exclusion of local communities and the exclusion of youth. It can be particularly harmful for Africa’s youth to see their surrounding environment changing without their participation. Increasingly, infrastructure megaprojects are criticised as often creating more harm than good in local communities.

Threat to Infrastructure – The threat to the infrastructure itself comes from failing to ensure sustainability and resilience. Infrastructure overly reliant on foreign skills can later run into maintenance problems when these skills leave. Similarly, projects that begin without the full support of local communities are less likely to be valued, maintained and protected over the long term.

Reputational Threat – African governments and businesses are engaged in a constant battle to reduce the perception of risk around investing in Africa. By structuring investments and projects in a way that excludes local businesses and communities, investors are often creating conflict and often generating risks to their investments that did not previously exist.

Africans Often Pushed Out Of African Infrastructure Build

UK based NGO Engineers Against Poverty has highlighted that “much of the funding currently invested in infrastructure in low-income countries does not benefit contractors, suppliers and workers from these countries.”

According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, only 16 per cent of construction (on projects over $50m) is accounted for by domestic private sector construction companies. The commission states that “African construction companies generally remain too few, too small and too underresourced to compete effectively with international private companies for government and development finance institution infrastructure projects.”

According to Deloitte, Chinese contractors alone constructed an estimated 30 per cent of all major projects in Africa in 2020.

African firms accept that multinationals will play a major role in infrastructure megaprojects. However, there is an expectation that within those projects partnerships should be built with local firms and with a commitment to knowledge transfer and local skills development.

A 2018 report on the impact of foreign construction companies in Ghana by Christopher Amoah of The University of The Free State challenged the understanding that “foreign firms are also perceived to be the conduit through which the human resource base in developing countries are enhanced as a result of managerial experience, entrepreneurial expertise and technological skills they posses”

The report in fact concluded that “the presence of foreign construction companies in Ghana has not had any positive effects on the local contractors with respect to the transfer of knowledge and technical know-how. Thus, local contractors are outcompeted in the execution of major developmental projects embarked on by the Ghanaian government.” The report was compiled by interviewing local company owners with the findings demonstrating that Ghanaians feel locked out of their own nation’s infrastructure build. It is a situation played out across the continent.

Funding Models Favour Foreign Firms

The major problem facing African governments is the lack of funds for infrastructural projects; hence, they rely on loans from multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monitory Fund, or from countries in Europe, Asia and South America.

Chinese firms are often able to secure funding at favourable rates from state finance institutions, a path simply not open to African construction firms.

Data on African construction sector projects over $50 million in size confirmed that, in 2013, 57 per cent of infrastructure projects were owned by Governments. However, only about 6 per cent of the funding for these projects is from African governments. The sector is reliant on foreign capital.

This international capital comes with strings attached; foreign firms are given preference when contracts are awarded.

This is where Mr Mnyani calls for change saying; “As Africans, we can’t treat investors like they are doing us a favour. They invest because they will get a return on their investment in due time. Ensuring maximum benefit for local economies and communities must be structured into investment agreements.

“Investors, however, do have the right to oversee the projects because it is their money and they must be sure of a return on investment. Clear guidelines on local content must exist for foreign companies to follow. It would be in the best interest of governments and contractors to subcontract locals and make that non-negotiable.

“I am a big believer that we must legislate to arrive at the destination we want to be. Financiers like the World Bank must also be sensitive to that and have such structures observed in their contracts.

“Change is required at the top – at the level of the IMF and World Bank – to ensure Africa is built by Africans and that projects have a legacy of employment creation, skills transfer and community impact.

“Often the international financiers will insist on work going to European or Asian firms. This is counterproductive. African firms have the capabilities to deliver and the understanding of how to work with local communities.”

Local Content Policies Need Local Skills and Leadership

‘Local content’ in construction refers to the involvement of local enterprises and labour in planning, design and construction services, as well as the involvement of local service providers and manufacturers in the project supply chain.

Local content policies were initially created to regulate the oil & gas sector and now in some countries, such as Botswana, policies exist within the construction industry as well.

Local content is complex. Local skills must be developed to match the work being undertaken. Creating the environment in which economies can prosper in line with local content policies requires buy-in from all stakeholders: governments, investors, financiers, local firms and higher education institutions.

The results thus far are mixed.

Mr Mnyani says “There remains work to be done to make local content policies work in the real world and not just on paper.

“Often, it is a box-ticking exercise.

“They are not effective in many countries because they are not legislated properly. It becomes difficult to enforce. Legislation must be clear so that foreign investors are clear on what percentages must be handed to local companies.

“The IMF, World Bank and other bodies must also take up local content as policy and stop imposing contractors on Africans. In our case, we are contractually obligated to work with Botswana based companies and that is how it should be.

“Doing this will eliminate cases of foreign workers working on all the big projects we see in places like Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Companies like Khato Civils must advocate for local content policies while also educating our governments on the need for this. We are pro-partnership and we should never accept to be dominated by foreign companies because Africans must be involved in projects from A to Z.

“Most multinationals train local companies just to comply with local content policies. Doing it just for compliance is a recipe for failure. Multinationals must make it part of their policy and genuinely help enhance local capabilities.”

Khato Civils Inclusive Approach: Five-Point Local Impact

Using the Botswana 100km pipeline project as an example, Mr Mnyani explains how Khato’s approach of engaging with local companies removes the 5 development threats and replaces them with five benefits:

-

Economic Impact: Inclusive Growth

Economic impact was ensured by creating maximum local participation along the supply chain.

However, the long term economic value of such projects lies in the development of local skills development and creating opportunities for local firms.

“We might have to bring along some skilled workers, but semi-skilled and labour services have to come from local communities.

“Suppliers in both Botswana and South Africa have benefited immensely from our activities over the past few months. Most of our pipes, steel and valves were procured from South African companies and we also invested a lot in the economy of Botswana.

“Our contribution to the economy is thus very clear and the government of Botswana is very serious when it comes to keeping money flowing within the country.

“We believe in the value chain. We have to properly investigate the local market and see who can provide value to our projects within any region we are working in.

“The Botswana project demanded that we have at least 30 per cent of the work done by a local company.

“We adhered to that and even subcontracted some more work to other local firms. 80 per cent of the subcontractors we worked with were from Botswana and we did this to ensure that the local economy benefited from our work.

“We will look to help develop the expertise of local firms while also giving them much-needed experience. A lot of skill is available locally but needs to be nurtured and modernised.”

Khato Civils does this well and we also mentor small companies to help them develop capacity.”

-

Social Impact

The largest impact Khato Civils created came from recruiting workers from all communities along the 100km the pipeline covered. Similarly, local leadership is consulted at each point along the pipeline.

The company additionally looked to build a legacy along the length of the pipeline and not only in the capital city of Gabarone.

“During the project, we identified several tributary projects that could be worked on along the pipeline. We believe in investing in local communities as we pass through. A lot of the tributary projects we did were suggested by local community leaders with one being the construction of a house for a destitute family.

We also did a classroom block in Selebi Phikwe which pleased a lot of people in the area. The cost of such tributary projects is wholly on us; none of it is passed to our clients. For us, it’s about not only completing contractual projects but also leaving a good name and a lasting legacy.”

-

Sustainable Infrastructure

Engineers Against Poverty highlight that “Reliance on foreign enterprises to design and construct facilities often means they are not sustainable as the expertise may no longer be available once the construction is complete.”

This is a common theme across all areas of African development, from education to health to infrastructure. The only way to ensure the long term sustainability of projects and infrastructure is to put locals at the heart of the project, ensure knowledge transfer takes place and ensure ownership of the project is in local hands.

Khato Civils stress the importance of partnerships and long-term planning to ensure sustainability.

“Before partnerships can be formed, there has to be a clear articulation of what the master plan is. Each African country must clearly define its vision and form a core around the vision before forming enabling partnerships.

“The vision must also be long term with a 10 to 15-year outlook. We must have master plans for roads, energy, water and all other sectors. The master plan must also have a clear model of operation and an articulation of how it will be funded. Once the vision is clear and well-drafted, it can be packed and sold to investors and partners who will then buy in.

“If we set out to build new infrastructure, we must know what that means in every detail.”

-

Security and Conflict Reduction Impact

Working productively with local communities, labour organisations and traditional leadership is key to reducing conflict around projects. Domestic construction firms are best placed to understand their local communities.

“You can’t just undermine what local companies can do.

If you show up in these communities biased and not willing to engage, you will fail. In Mozambique for example, we have seen cases of project failure because multinationals had little respect for the locals. It can directly lead to protests, strikes or sabotage of projects.

You should always have a mindset of working with the locals to avoid animosity. If we are serious about the health of the economy, we must accompany aid with capacity development.

The mindset of feeling superior to the locals needs to go if projects are to work properly across the continent.

“In Botswana, our approach was to reduce cases of conflict as much as we could. Our recruitment system had to change and become more inclusive.

We ensured that we had workers from each village where the pipeline was crossing through.

Consultation with local leadership could mean talking to traditional leaders, councillors, members of national assemblies and community leaders. Consultation can be very complex and time-consuming, but it is all worth it to eliminate any problems along the way. This is our process everywhere we go and we don’t intend to change it.”

-

Reputational Impact

Delivering impactful projects in a manner that avoids conflict, reduces risk and brings economic benefit is one in which governments and the private sector must collaborate. The result of such projects is to steadily make that risk vs reward ratio more favourable.

“With the pandemic still with us and the global economy on a downturn, investors are very selective about where to direct their money,” says Mr Mnyani.

“The real challenge is that investors are holding on to their money when African countries are doing everything to build up infrastructure.

“If you look at most of the major projects happening on the continent you can see countries have to get creative when it comes to attracting funding. There must be a clear value proposition and return on investment promise so that wary investors can feel at ease.

“Building a strong reputation upon a base of good governance, project delivery and impact in communities will attract financiers as they become convinced the risk versus reward ratio works in their favour.”

“Governments must put together attractive packages that will showcase their countries as attractive investment destinations. We must show investors why African markets are competitive investment destinations when compared to places like Southeast Asia where investor confidence is already high.”

Project Result: Delivered On-Time and Below Budget

In the case of the 100km pipeline project in Botswana resulted in little to no conflict and disruption and the completion of the work ahead of schedule.

The project was delivered in under 12 months, and Botswana’s Water Utilities Corporation credited working with Khato Civils as saving them 1.2bn Pula (over USD 100m) as compared to similar large scale water projects.

The Alternative Road: African Firms as Economic Drivers of Inclusive Growth

It is clear that with only 16% of construction work going to local firms, African firms will struggle to grow their local economies and generate much-needed employment and training opportunities.

Ambitious African politicians often like to cite Singapore as an example of economic development done right. Forty years ago the local construction industry in Singapore was seriously underdeveloped. Now local firms are fully competitive in their home market and win significant numbers of projects overseas.

Singaporean contractors recognise that government improving the operating environment and providing financial incentives was key. The industry was built through local participation in public projects.

Similarly, governments have got to lead across Africa in creating the enabling environment for local firms to prosper. The private sector meanwhile must ensure that knowledge transfer and skills development continues in each and every project across the industry.

Mr Mnyani concludes by stressing the importance of public-private partnership for Africa’s development by saying “Many African countries have established public-private partnership offices. These should help articulate the vision for development. We must make public-private partnerships less restrictive in order to facilitate investment.

Governments must also create a conducive environment built on stability and non-interference from the government.

Companies must position themselves to thrive while working with the government and all other stakeholders. Every country and company must put aside a capacity building budget because that is how you grow. Training and capacity development must become key to ensure real empowerment comes to communities.”